Why did you choose a career in architecture and design?

I was very interested in art throughout my childhood. From model making to art pieces, drawing cartoons – I really wanted to be a cartoonist. My first architecture-related art piece is a pencil sketch of HSBC headquarter in Hong Kong when I was in the fourth grade. As I got older, I concluded that being creative, gave me great satisfaction. Architecture seemed to be an obvious choice for me, apart from being an artist or designer. One of my teachers, who understood my interest, suggested I become an architect.

Tell us about your background prior to joining Farrells

I grew up as a Melbournian boy and studied architecture there. I studied every possible art related subject I could enroll in – photography, wood making, ceramic, graphic communication, pencil sketching, interior design, product design etc. While studying architecture at the University of Melbourne, I had been working part-time within various architectural practices – big and small, international and local, design and commercial architects. I always think thatI was so lucky to experience so much before working in the

real world.

I started as an architectural designer at Farrells. I first worked in Farrells’ Hong Kong in 2000 and I have also worked in their UK and China offices. When I was in the London office I worked quite closely with Sir Terry Farrell, the founder of Farrells, which was inspirational as well and an honor. This year is Benjamin Lau’s 20th anniversary at Farrells. Leading a number of Farrells’ large-scale and high-profile architectural, award winning projects, he tells us where his inspiration comes from, how urban design has evolved over the years and his plans for the new Farrells office in Australia.

Where do you get your design inspiration from?

I am a very hands-on designer and I always start my design process by sketching at the outset. I am still sketching a lot nowadays, which is the only way I can get my creative brain working. But my design inspiration also comes from talking to different people and collecting objects. These objects are often related to a story, a piece of history or local culture of a place, which have found themselves within a number of projects I have worked on.

What have been the biggest hurdles and challenges you encountered in the profession?

Architects and masterplanners are often seen as sole creators. A good design is created through respect, collaboration, communication and understanding with everyone in the team, community, stakeholders and often general public in a much wider context. I am proud to be Australian-Chinese who has been educated under the British system and so, understands both eastern and western cultures. Understanding of local culture is one of the keys for architects when you work outside their home towns. Working with Farrells and due to the nature being an architect, I have travelled extensively to many countries, broadening my perspective and understanding different local cultures.

What have been the biggest highlights?

I am sure there were many memorable moments – when you get a bit older you just don’t remember them all! One of them is a month-long secondment to Beijing to lead the design of the China Zun competition. The entire design team of over a hundred people had been working continuously for a month and I made some amazing memories during that period. Another memory would be holding up an industrial sized air blower within a 3m diameter inflatable bubble to test out the exhibition installation at Peak Tower in Hong Kong, at midnight, for Farrells’ Asia Pacific exhibition in 2014. Last but not the least, is that I was made as a design director at Farrells when I was at 31 – the youngest design director in the history of our office.

Postmodernism in architecture/ urban planning nowadays – how do you think it has transformed/ evolved? And what is your favourite project to date?

Sir Terry Farrell is undoubtedly the forerunner of postmodernism in architecture. When talking about postmodernism, one usually thinks about elaborated decoration, colorful facade and oversized classical ornaments, like our MI6 or TVAM in London. I wouldn’t say that we are still designing buildinsg in postmodern style, but our design approach and philosophy is still rooted from those principles. One of my favorite pieces of work– Clifton Nurseries in London’s Convent Garden –which was built as a temporary structure built in early 80s.

Some of its design principles are still highly applicable to our architecture and urban design nowadays – things like its public realm approach, context response to the St Paul’s church directly opposite, and the use of advanced building technology. It also reflects my belief that there is no such thing as ‘job done’ in urban design. Masterplanning is about defining some principles and creating some strategies for a place to develop. And of course, Peak tower on the top of the Victoria Peak, is another good example of contextual architecture design. Also KK100 in Shenzhen, China. The design is really innovative during the time when it was built, it is a really ‘singular’ building.

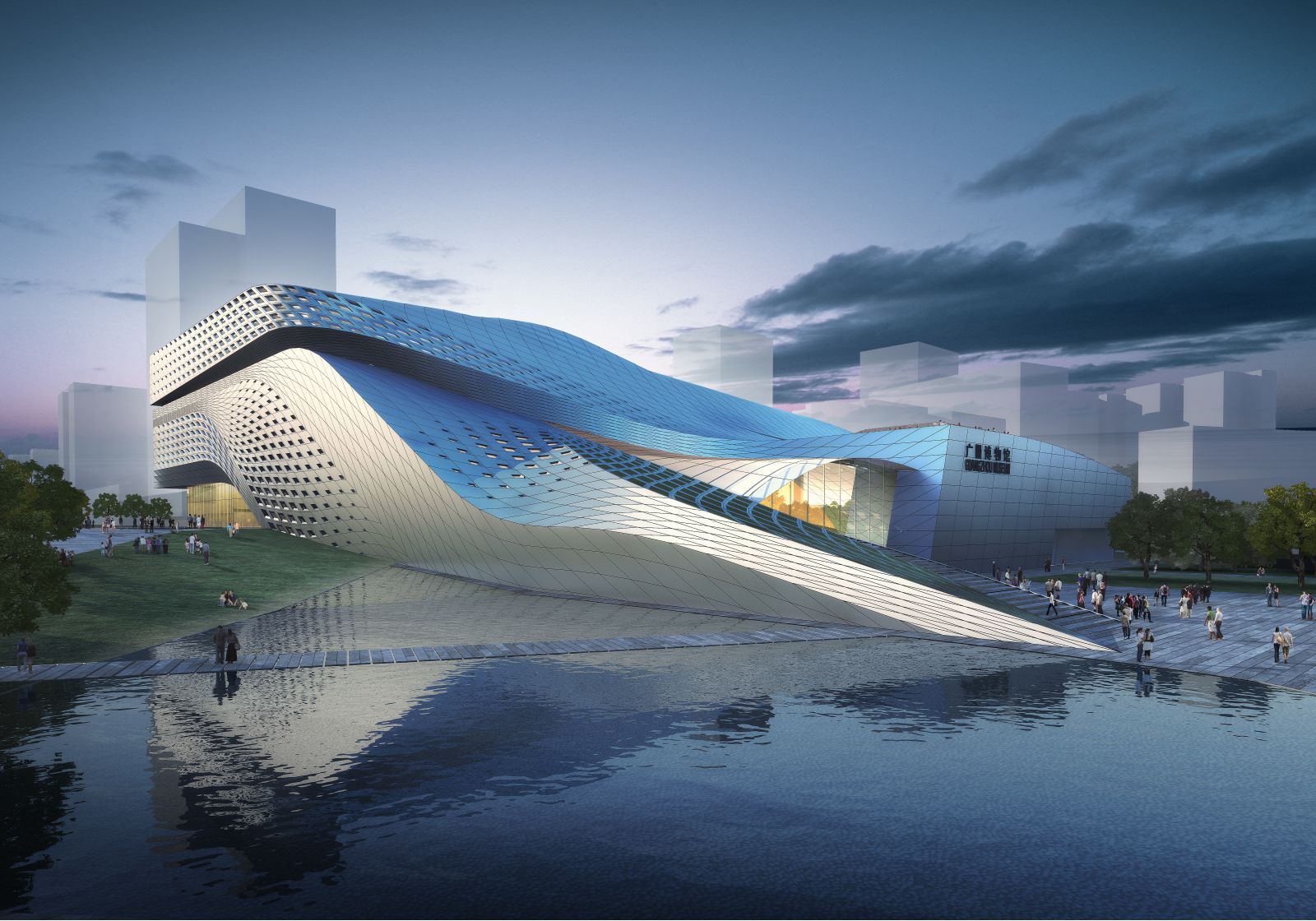

The canopy design makes it appears to be ‘merged’ with the building, instead of being an additional part. This singular character set the building itself to be very different from the super high-rise at that time, which they were rather standardized to have separated looking top, middle and bottom parts. Some of our best ideas are unbuilt such as New Dehli station and a mission center for Korea’s Yonsei University – a strong symbolization of Christianity, Guangzhou cultural museum and a futuristic TV tower in Wuxi, China. The reason I like about these projects is that their designs are all ahead of their time with meaningful stories and strong cultural reference. While most professionals are specialized in a particular type of building, I am probably rare in not having a ‘niche’. I designed different building typologies, varying in scale. My projects range from a single family house to the world’s largest train station, from super tall tower to underground shopping centres as well as, museums, hospitals, hotels, broadcasting studios, cultural centers, station depots, police stations etc. This is the excitement of working with Farrells, our design freedom and exploration is limitless.

What is it like to work at Farrells?

Farrells has a long standing history as an international design house. We have multi studios globally but each one has around 50-60 staff to the uppermost of a hundred, which I think it is the right scale for us to be free from limitations in creativity, duties and commercial considerations. You get to know everyone in the office and we have a relatively casual, less hierarchical company structure to protect. I will continue to have a role in the ‘middle’, connecting all the designers and continue to encourage young design talents, which I am passionate about.

What do you think Australia can learn from the likes of Hong Kong, where urban planning is modeled around high density design?

Rapid urbanization is something that we all have to face positively. Melbourne is projected to be the most populated city in Australia and by definition it would become a megacity by 2070. Hong Kong has been developed as a ‘linear’ city due to its unique topography and urban growth along railway lines. Cities in Australia such as Melbourne and Sydney have been developed quite differently. Design experience, technology and principles are adaptable, but we need to consider and respect every place’s local history, culture, social economy and behavior sensitively.

Farrells is known as the expert of architectural designs for high-density urban areas also TOD (Transport Orientated Development) – How do you think this strength can be applied in the Australian context?

Australia has started to pick up the TOD model in the past decade as well. There have been some good TOD developments, located next to offices or residences, which is very convenient, and some may be more exaggerated than Hong Kong. The density ratio is 18:1, which is quite challenging, so I will definitely bring Hong Kong’s TOD concept and experience to Australia. But we will also put effort on maintaining and respecting the Australian context.

Because urban design should not be directly applying the design or planning from one place to another, they should not only applying innovative elements, but also respect the local culture and community in order to create a better place for everyone. Melbourne and Sydney’s city development is similar to London’s. It has one or multi numbers of dense centers surrounded by a widely spread outer suburban area. The key is how provide an efficient transportation network between city center(s) and suburban areas. Then it is about creating a 24 hours ‘Work, Live and Play’ city center within a very compact footprint with high density. The most obvious answer would be to create an integrated station development with mixed-use. To me, TOD is an extreme of sustainable living. It offers a very efficiency transportation model. Source and images Courtesy of Farrells.